Golden Pipeline

A time capsule of water,

gold & Western Australia

A project from the National Trust of WA

A self-guided drive trail between the Perth Hills and Western Australia’s Eastern Goldfields. Go with the Flow. Follow the water to discover more about the audacious goldfields water supply scheme and Engineer CY O’Connor.

“Future generations, I am quite certain will think of us and bless us for our far seeing patriotism, and it will be said of us, as Isaiah said of old, ‘They made a way in the wilderness, and rivers in the desert”

The Scheme Need for the Scheme

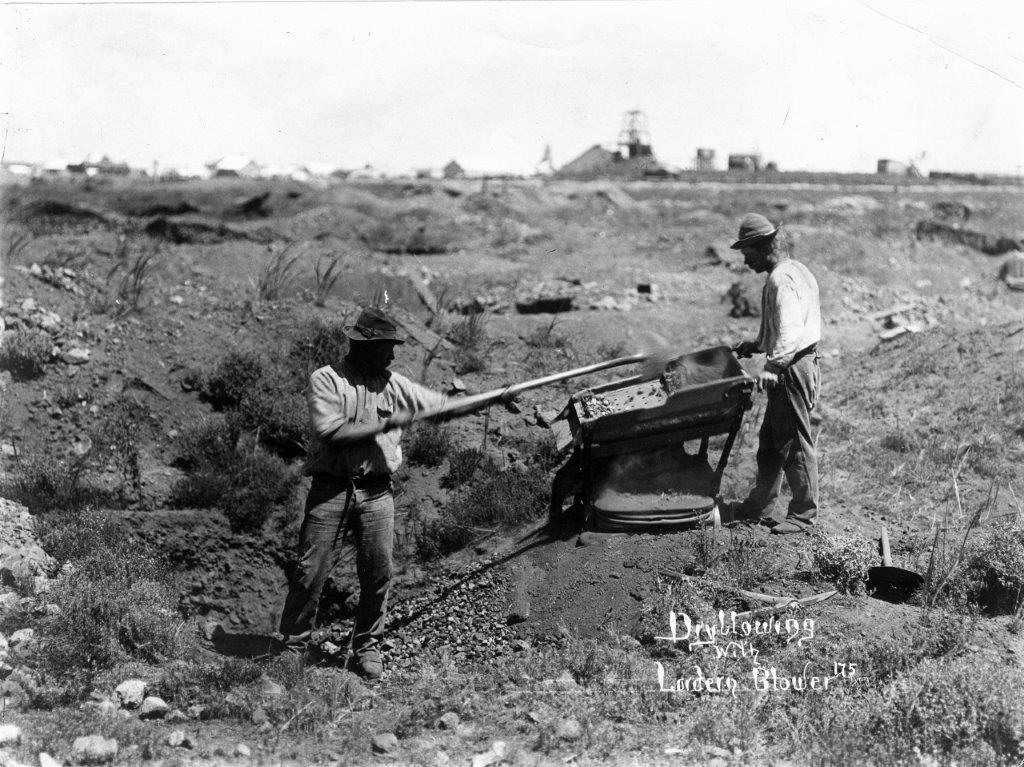

Dryblowing

The dryblowing machine is almost as synonymous as the wheelbarrow with the 1890s Gold Rush and early days on the Eastern Goldfields.

Water, the best medium for separating gold from “paydirt”, was so scarce that water races or sluices used on contemporaneous goldfields were out of the question. For example, on the well-watered West Coast of New Zealand, an engineer designed a water race for the Hohunu goldfields.

That engineer’s name was CY O’Connor and conditions he encountered on coming to WA years later were to be quite the opposite. He had to find a way of supplying permanent fresh water for the Eastern Goldfields and famously recommended the pumping scheme (including the pipeline) that operates to this day.

On the waterless Coolgardie goldfields before the pipeline, diggers used a technique known as dryblowing that takes advantage of gravity and the high density of gold and uses wind rather than water to separate gold from dirt. They had to find a way of extracting the precious metal that didn’t use the arguably even more precious liquid.Julius Price described what he saw round about Coolgardie in his 1896 publication The Land of Gold as the “rough, primitive method of ‘winnowing’ the alluvial ground”.

In its simplest form dryblowing was done by hand using dishes or pans. New Zealand prospector John Aspinall observed paydirt

emptied into a dish, then by dropping the stuff from a high elevation into another dish at his feet and throwing it into the air and catching it again aided by panning into imaginary water using the back of the hand to remove the lighter materials, the dryblower is able to pick up all the specks of gold, the fine stuff not being sufficiently profitable to save…

With hundreds of prospectors on the fields the clouds of dust emanating from dryblowing were visible from a great distance. Apparently dryblowing could be heard as well as seen.

In Coolgardie Gold Albert Gaston wrote I could see from my camp numbers of men working on a flat, and as I approached them I could hear a peculiar sound. Great clouds of dust were rising from the scene of their operations. The dryblowers were at work and the sound was made by them pouring the wash dirt from one dish to another.

The better-equipped prospector had “Rockers’ or Shakers”. These contraptions were flexible frames with a series of trays and screens which, when shook vigorously, allowed the dust to blow away, leaving the heavier gold in the bottom.

The terminology is not exact but strictly speaking what distinguished a “shaker” from a dryblower (the machine rather than the operator) was the addition of a bellows. So the dryblower is thought to be an improvement on the shaker. Operated by foot, the bellows blew away fine dust leaving the larger grains and slugs of gold.

New Zealand prospector John Aspinall, visiting Hannan’s (officially Kalgoorlie by then) in April 1895 described the various contraptions, many of which had hoppers into which the paydirt was fed:

Some called “Rockers and Shakers” are very crude affairs, being simply a series of square sieves which are rocked from side to side, or being set on flexible legs are shaken backwards and forwards. As a rule no attempt is made to save gold finer than a pin’s head. The best machines have, besides the rocking motion a pair of bellows which keeps a blast of air going through the machine.

Dryblowing was not actually a WA invention but was perfected on our fields. Arguably Teetulpa in South Australia in the 1880s was the testing ground for dry blowing techniques. The Adelaide Advertiser of October 22, 1891 carried news of a machine invented by a Mr Paynter that offered a fast efficient dry method for extracting gold from alluvial ground. Paynter machines were later used in WA and the basic design copied by other manufacturers.

You can usually see a wonderful example of a dryblower in the Kalgoorlie Museum. What makes it particularly special is that it is a Lorden dryblower, manufactured in Fremantle and the frame is U-shaped, all the better to fit over a camel’s hump!

Battye Library. Dryblowing with Lorden Blower.

Battye Library. Dryblowing with Lorden Blower.

Dryblowing was a thirsty and dirty business, made all the worse by the lack of water. As J.C.F. Johnson wrote

“the great objection is first, the large amount of dust the unfortunate dry blower has to carry about his person, and secondly, that the peck of dirt which is supposed to last most men a life time has to be made a continuous meal of every day.”

But while they complained about dust, dryblowers hated mud even more. The rains of July 1893 saturated the ground to such an extent exasperated diggers had to dry the dirt for three days before dryblowers could be used.

Sunday was the only day diggers took off work and they used it to rid themselves of the red dirt encrusting them and to beat it out of their clothes. Some went to church. A favourite “round” about dryblowers (men, not machines) was sung at Salvation Army meetings in their Coolgardie Hall, to the tune and metre of “Three Blind Mice”.

Three dry blowers

See where they ran,

They all ran up to the Army Hall

And there gave heed to the Saviour’s call

And down at the Mercy seat did fall

Those three dryblowers.

Explore

Click on any map section or place below to discover The Golden Pipeline.

Northam to Cunderdin

Explore section two